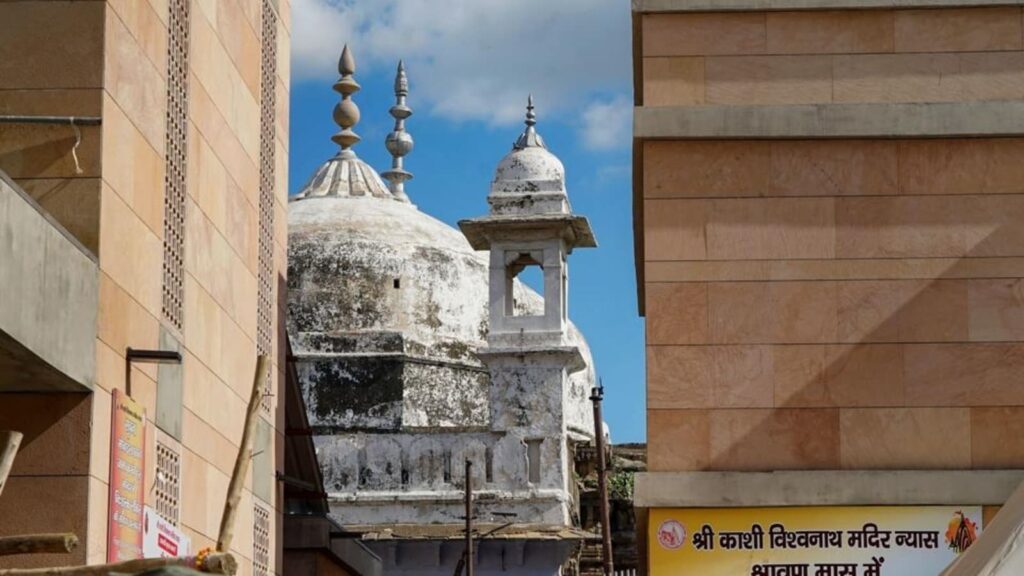

Roughly 14 months after a court-ordered survey of the Gyanvapi Masjid complex raked up a centuries-old dispute, another survey ordered by another local court threatened to stoke sectarian tensions on Monday before the Supreme Court (SC) stepped in and halted the exercise temporarily. For about four hours, even as lawyers representing the mosque committee rushed to the apex court, frenetic scenes unfolded in Varanasi where officials from the Archaeological Survey of India (ASI), displaying unusual alacrity, descended on the complex early in the day to conduct a survey aimed at ascertaining whether the mosque was built over an existing structure – a contention by a clutch of Hindu petitioners.

The developments make two aspects of the case clear. One, that the Gyanvapi proceedings have become a test case, especially for Hindu groups who are using legal petitions in courts to drive a new temple movement (which, unlike its earlier avatar from the 1990s, isn’t using street mobilisation as a tactic, but is pushing for legal change). The petition of Hindu women asking for the right to regularly worship Hindu idols inside the complex is only one of a batch of similar petitions in Varanasi, Agra and Mathura. The top court said last week that early disposal of cases connected to the Krishna Janmabhoomi dispute (again, Hindu petitioners say the Shahi Eidgah mosque was built on a plot that belonged to the Sri Krishna Janmabhoomi Trust) was preferable, and that it would lay down norms. But given the sensitivity and political implications of the cases, such norms – unless applied more universally – might serve a very limited purpose.

What makes Gyanvapi such a good test case? It is because it appears to have found a way around the 1991 Places of Worship Act, which was envisioned to forestall precisely this kind of legislation. Drafted at the height of the Ram Janmabhoomi movement, the law – which locks the religious character of shrines as they existed at the moment of Independence – was meant to protect the social fabric and prevent future disputes. It continues to exist in the statute books, but appears powerless as one dispute after another mushrooms. Proceedings before SC are pending on this question, and the Union government is yet to tell the court whether it will review, scrap or defend the law. Unless the Centre makes its stand clear, or the top court decides on its validity, expect many similar grievances to be dredged up and brought before lower courts, disrupting communal amity. For now, a law meant to protect India from such a future hangs in a strange liminality – existing but effete.

Enjoy unlimited digital access with HT Premium

Subscribe Now to continue reading